I recently attended a reunion and ran into–of all people–Bond, James Bond.

OK, I didn’t actually run into 007 in person. I came upon him in book form. And the “reunion” is part of a writing/blogging project in which I’ve been revisiting some of the influential books of my youth (the very blog you are reading now, dear reader!).

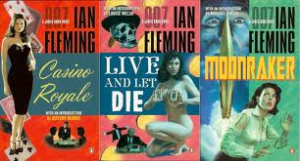

I have recently finished reading, for the first time in forty-five years, the entire Bond series (the fourteen books Ian Fleming published between 1953 and 1966).

I faced our reunion with trepidation. Bond was one of the great heroes of my youth: the suave, cool, mysterious figure who always seemed to be there when my adolescent self needed him. Bond showed me how to navigate the treacherous waters of manhood, helped initiate me (and how many others?) into the coded male world of drink, cars, friends, and women.

What would I think of 007 today? Even more daunting, what would he make of me?

Of course, James Bond has never really gone away. There have been attempts by other authors to continue Fleming’s literary legacy. And, more pervasively, there has been a long, mostly undistinguished string of films to keep his image and memory alive. (Although, happily, the most recent Bond films–especially the excellent Skyfall–have restored some of his luster.)

But the film Bond is one person and the book Bond, the one who had such a profound influence on me, is quite another. Over the years, the films had gradually washed away many of my memories of the novels. Year after year, the film Bond had become more and more of a caricature, the villains more cartoonish, the plots more far-fetched and outlandish. Bond’s hold on me had gradually begun to fade . . . until our recent reunion. And the memories of what he had meant to the teenage me came flooding back.

Here are some of the lessons I remember learning from Mr. Bond:

- One never gets enough toast with his caviar.

- Women liked to be kissed suddenly and passionately, very hard, and with perhaps an occasional touch of cruelty.

- A Rolex is a heavy watch, but it is extremely dependable, especially when one is engaged in undersea espionage.

- One may order any number of drinks (the martini, shaken not stirred, is but one of many options). But the drink must be straightforward, made with basic liquors, and be prepared to specifications.

- Breakfast is the indispensable meal of the day and should be prepared just so. (A doctoral dissertation could be constructed out of analyzing Bond’s many pronouncements regarding breakfast.)

- It is imperative to have at least one trusty sidekick when embarking on a dangerous assignment. Preferably male, the sidekick should be loyal, fun-loving, and brave. Unfortunately, he will probably die–if not in the current adventure, then down the road. (Fear not, there will always be another trusty sidekick to take his place.)

- Beware beautiful women. They will inevitably betray you or provide the enemy with a vulnerable spot to attack you. If you happen to fall in love with one–perhaps even contemplate marriage–fear not. She will immediately and conveniently be disposed of by some plot device or other.

Why did this tall man with the rather cruel smile, the blue-grey eyes, the thick comma of black hair above his right eyebrow, have such a firm hold on me and my young imagination? I was an immigrant kid stuck in a grey, working-class suburb of New York City. Who was I to identify with this debonair lady-killer?

And yet, I devoured all that the books had to teach on how to be a cool guy: how to win at Baccarat, order caviar and a martini, drive a red-hot coupe, make love to an achingly gorgeous woman. Although I must confess that to this day . . . I have never developed a taste for caviar, never learned to play Baccarat, hate martinis, have never driven an Aston Martin or Bentley (I’m still not quite sure what a “racing change” is, even though Fleming mentions this driving maneuver in nearly every book), and my feeble track record with the opposite sex would have 007 tearing his hair out in frustration.

Nevertheless, I eagerly raced through the Bond books. My older sister usually purchased them. I didn’t have the courage to buy them myself: for a Catholic school boy like me they contained a whiff of the pornographic and sinful. Forbidden fruit, as it were. In retrospect, the sex scenes are laughably tame by today’s standards, but back then, ahh, even the merest hint of sex between two attractive, unmarried people was enough to get the imagination stirred (if not shaken). Even with their laughable clichés and soft-core absurdities, the love scenes gave me a fleeting glimpse of the possibilities of adult sexual relationships.

So how do the books hold up after forty-five years? Not bad. Not bad at all. There is more nuance than I remember. The earlier novels especially–Casino Royale (1953) and From Russia with Love (1957), which John Kennedy placed on a list of his favorite books–are actually more cold war thrillers than super-hero fantasies. The plots are more realistic, the stakes more believable. And, biggest surprise of all, there is some real emotional impact in the novels: Vesper Lynd’s suicide at the end of Casino Royale, and Bond’s terse one sentence response (“The bitch is dead now”) come as a shock in the context of the invariably breezy ending of most of the Bond films. At its best, Fleming’s writing is taut and lean, with hardly a wasted word.

Unlike the films, the literary Bond reveals something of an inner life–we are not talking James Joyce or Virginia Woolf, of course–but he does betray a sense of vulnerability, chides himself for the occasional mistake, has memories of the past (the film Bond seems to exist in a perpetual whizz-bang present), and generally comes across as more of a human being than the movie Bond ever does.

While the movie Bond can be something of a bore, the book Bond is altogether more shaded and easier to take. He even shows an occasional bit of self-awareness. After pontificating to his dinner companion about the merits of a fine champagne, he says: “You must forgive me . . . I take a ridiculous pleasure in what I eat and drink.” Vesper’s response could be taken directly from the Fleming/Bond playbook: “I like it . . . I like doing everything fully, getting the most out of everything one does. I think that’s the way to live.”

To a male of a certain age, the Bond books were the bible of style, an indispensable sourcebook for making the small but important choices boys must make on their winding path to adulthood. I loved poring through the books to see how Bond decoded character from the most insignificant-seeming clues. Any doubt that Emilio Largo in Thunderball is a villain is immediately dispelled when we hear his favorite drink: “crème de menthe frappe with a maraschino cherry on top.” In 007’s universe ordering such a fruity concoction is a signifier of irredeemably bad style . . . and therefore of bad everything. Largo might as well have “murderer of helpless kittens” tattooed on his forehead.

In From Russia with Love Bond nearly gets himself killed when he ignores his sartorial early warning system. He meets a supposed ally and immediately notices the man’s tie: “It was tied with a Windsor knot. Bond mistrusted anyone who tied his tie with a Windsor knot. It showed too much vanity. It was often the mark of a cad. Bond decided to forget his prejudice.” Beware 007. (Needless to say, when I first read From Russia with Love I did not, nor do I know now, what in the world a Windsor knot looks like. I suppose I could just google it, but prefer to let this remain a mystery.)

Occasionally this relentless fixation on the small details of everyday life results in an inadvertently funny moment. In On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1963)Bond, after months of anxious separation from the woman he loves, finally reunites with her and has this romantic exchange (spoiler alert: Harlequin Romance dialogue this is not):

She took the turning, in Bond’s estimation, dangerously fast. She went into a skid that Bond swore was going to be uncontrolled. But, even on the black ice of the road, she got out of it and motored blithely on. Bond said, “For God’s sake, Tracy! How in the hell did you manage that? You haven’t even got chains on.”

She laughed, pleased at the awe in his voice. “Dunlop Rally studs on all the tyres. They’re only supposed to be for Rally drivers, but I managed to wangle a set out of them. . . .”

Is there any question that these two lovebirds are destined for the altar?

As I grew older and my literary tastes became more refined, my next heroes would come from Hemingway: Nick Adams, Jake Barnes, Frederic Henry. They are, like 007, men who exhibit a similar existential interest in doing things–even the smallest things–with style and grace. In a universe that is meaningless, random, and often cruel, how one does things–orders a drink, drives a car, deals with adversity–matters. Maybe, both Hemingway and Fleming seem to be suggesting, the how is all that matters.

But maybe we are getting way too heavy. I suspect that those of us who fell in love with the literary James Bond did so because he gave our younger selves so much that we needed back in our formative years: a glimpse of a life of money and glamour and style, a recipe book for manly behavior, some hints on how to deal with the opposite sex, and plenty of jolly good adventures.